“The study of modern mystical Qabalah is almost exclusively in the hands of Gentiles, and orthodox Jewish scholars know little or nothing of its literature and nothing whatever of its mystical significance.”

— Dion Fortune, English Occultist, 1930

Recently, I read Psychic Self-Defense by early 20th century author, psychic and mystic Dion Fortune. To protect against negative influences, she recommended visualizations and prayer practices that I recognized from Jewish prayer. I found it fascinating that a British, non-Jewish occultist from 100 years ago saw Kabbalah as so central to her work.1

It occurred to me that there was indeed a time in the 1800s and 1900s when most Jews knew nothing of Kabbalah. At the same time, non-Jewish spiritual groups were discussing it, using some of its practices, and reinterpreting it in their own creative — if not, at times, grossly misinformed and even anti-semitic — publications.

I wrote to Israeli academic Boaz Huss, an expert on this phase of Occultist Kabbalah. Through our correspondence I learned about where it came from and how it has developed adjacent to the relatively recent reawakening of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism within the Jewish community today. After reading a number of articles he sent me, I finally feel ready to write a post about one of the most frequent questions I have been asked in the last two years:

What is Kabbalah anyways?

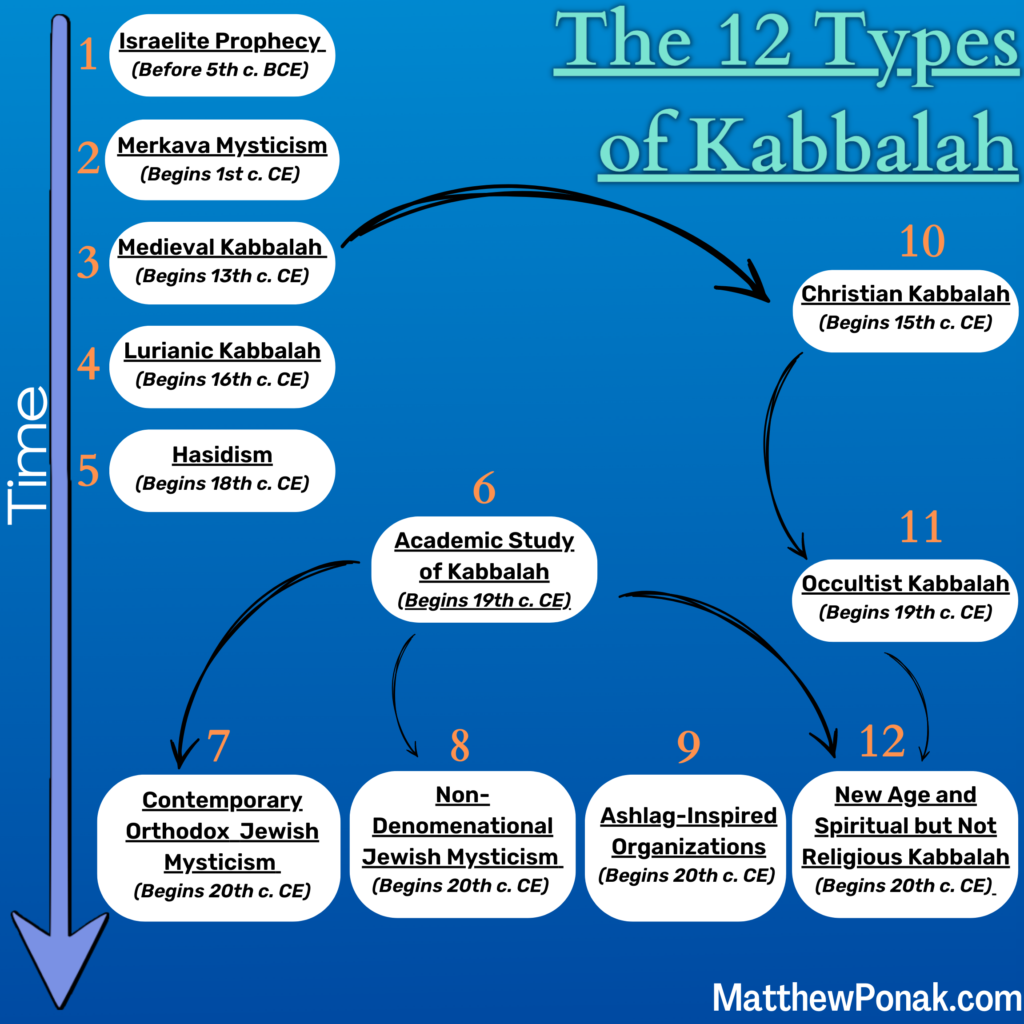

For a lot of people, the great number of ways the word “Kabbalah” is used can be overwhelming. Today, many different groups (often competing with one-another) teach divergent practices and philosophies of Kabbalah, often with unique origin stories for how this type of mysticism came to be.

So, to help cut through the confusion, I give you the:

12 Types of Kabbalah

Whether you spell it with a “K” a “C” or a “Q” this form of spirituality means a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

Before you get into the 12, here are two main ways the term Kabbalah is used within Judaism:

- Kabbalah is a type of medieval Jewish mysticism first recorded in France and Spain.

- Alternatively, Kabbalah is a term which refers to all Jewish mysticism throughout the ages.

And here’s a definition of mysticism: The pursuit of the Divine through direct experience. Instead of believing in Ultimate Reality, students of mysticism strive for encountering what lies beyond ordinary consciousness and perceptions.

Broadly speaking, Jewish mysticism emphasizes the effects that experiencing God has on a person’s inner life and actions. The “fruits” of Jewish mysticism are the refinement of our minds, emotions, and actions.

With those distinctions and definitions in mind, here are the 12 types.2

1. Israelite Prophecy

(Before 5th century BCE)

This category is arguably the most controversial to include here because many people do not think the prophets were kabbalists. That being said, some people do, and this is an inclusive list! Prophecy can fall into the category of Jewish mysticism (and therefore Kabbalah) because it involves a connection with Ultimate Reality that affects the prophet and those around them in profound and meaningful ways.

In the era of the Hebrew Bible, prophets heard God’s voice or received visions and carried out the will of the Divine — often bringing weighty messages to powerful kings. Within this tradition whose origins are difficult to trace, there are different types of prophetic callings. One type is prophets being chosen by God without obvious prior preparation such as when God spoke to Moses from the burning bush (Exodus 3). Another type involves training through prophetic discipleships, such as the prophet Elijah who trained his successor Elisha (1 Kings 19).3

2. Merkava Mysticism

(Begins 1st century BCE)

Early rabbinic texts contain fragments of a mysticism that involved travelling through celestial chambers and seeking hidden wisdom from different levels of angels. The goal of many ascents was to encounter the highest angel Metatron or to glimpse the Divine Throne.

For a sample of these writings translated into English see Meditation and Kabbalah by Aryeh Kaplan, pages 42-54.

3. Medieval Kabbalah

(Begins 13th century CE)

When academics say “Kabbalah” with no other qualifications, this is the movement they are almost always referring to. Medieval Kabbalah was a mystical movement that explored the many layers between our world and the Infinite (aka God). These layers are known as the Ten Sefirot and constitute a stage-by-stage emanation of the Divine into the physical world. This ladder of emanation, when reversed, was a ten stage journey from the human world back into the Infinite.

There was likely a pre-existing oral tradition for Medieval Kabbalah, but the earliest known writings are from Isaac the Blind, who lived in Provence, France. The most influential book from this era was the Zohar, an incredibly detailed and varied interpretation of the Torah through the lens of the Sefirot. The Zohar is attributed to the teachings of the 2nd century Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. However, since it was written in a unique Spanish-influenced form of Aramaic, it is considered in most academic scholarship to have been composed in the late 13th century by medieval rabbis..

Ecstatic Kabbalah also flourished during this period, most notably in the writings of Abraham Abulafia. Its writings were more explicitly experiential than the Zohar and it held the personal encounter with the Divine as the highest kabbalistic ideal.

For samples of this type of Kabbalah see Zohar, the Book of Enlightenment by Daniel Matt and The Mystical Experience of Abraham Abulafia by Moshe Idel.

4. Lurianic Kabbalah

(Begins 16th century CE)

This influential movement was centered around the teachings of Isaac Luria, a mystic who taught for only two years in Safed (Eretz Yisrael3) before he died in his thirties.

He taught a cosmology of shattered vessels, holy sparks, and tikkun olam [repairing the world]. This narrative described how the initial spiritual foundations of the world were shattered. Subsequently, holy sparks of Divine light as well as unholy shards were scattered and misplaced throughout the world. In the Lurianic system, a Kabbalist’s role is to repair the cosmic dimensions by realigning the sparks and shards through elaborate visual meditations paired with ritual acts.

To read about Isaac Luria and his teachings, see Physician of the Soul, Healer of the Cosmos by Lawrence Fine.

5. Hasidism

(Begins 18th century CE)

This was a popular spiritual movement that started in Eastern Europe and emphasized experiential mysticism, joy, simplicity, embodied practice, and transformation.

Hasidism is often traced to the Ba’al Shem Tov, a nature mystic and shamanic healer. Equally if not more important to its formation, however, was the Maggid of Mezeritch, a student of the Ba’al Shem Tov who trained and inspired dozens of students who went on to spread this new message across Eastern Europe. Today, there are hundreds of Hasidic denominations organized around individual spiritual leaders called Rebbes.

For a classic compilation of Hasidic stories read Tales of the Hasidim by Martin Buber. For primary sources of early Hasidic teachings on the Torah see The Light of the Eyes by Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl, translated by Arthur Green.

6. Academic Study of Kabbalah

(Begins 19th century CE)

In the modern era, Jewish academics began to study Judaism through a historical and critical religious lens. The single most influential scholar of Kabbalah was Gershom Scholem (1897-1982) whose lifelong research yielded an understanding of Jewish Mysticism that had distinct eras and phases. Without his work and the of subsequent modern scholars, the view that Kabbalah had originated with the prophet Moses around 1500 BCE may never have been challenged. The Zohar’s authorship, as well, may have continued to be attributed to a 2nd century sage. Archival research also uncovered lost manuscripts and schools of Kabbalah that had been almost entirely forgotten by the modern era. The Academic Study of Kabbalah continues today and has had wide-reaching influence on many of the newer forms of Kabbalah today.

A foundational book in this field is Major Trends of Jewish by Gershom Scholem. See also Kabbalah: New Perspectives by Moshe Idel.

7. Contemporary Orthodox Jewish Mysticism

(Begins 20th century CE)

This new style of Kabbalah is taught mainly by the Ḥabad and Breslov Hasidic denominations, as well as in certain camps within modern Orthodoxy. It has had a wide sphere of influence and draws inspiration from previous forms of Jewish Kabbalah and sometimes from academic scholarship as well. The major differences between this form and the Non-Denomenational types (see below) are:

(1) the view that Kabbalah (i.e. Medieval Kabbalah and Lurianic Kabbalah by academic definitions) is as ancient and unchanged as the Torah itself and

(2) the view that Kabbalah is only truly viable within the framework of the ethical and ritual norms of Jewish law.

For an example of this style of mysticism see this article which articulates an Orthodox Jewish mythology of the origins and transmission of Kabbalah. This short piece of writing is fairly representative of the movement; it treats the mythology as true history and is often at odds with the findings of academic scholarship.

8. Non-Denomenational Jewish Mysticism

(Begins 20th century CE)

In the Jewish world of the last hundred years, exposure to psychology, psychedelics, shamanic traditions, eastern religions, as well as the integration of academic insights have produced many new forms of mysticism. Emerging progressive themes (especially outside of Orthodox Judaism) include pluralistic views of gender and sexual orientation as well as greater inclusion of practitioners regardless of ethnicity and religion. In general, meditation, body-centered practices, and a spirit of experimentalism are on the rise.

The two most prominent examples that span across the Jewish denominational spectrum are (a) Jewish Renewal (started by Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi) and (b) Neo-Hasidism: the wider movement within which Jewish Renewal can be situated. Neo-Hasidism began as teachers and students of all denominations started to explore and experiment with Hasidic mysticism outside of their traditional communities.

To learn more about this style of Kabbalah, take a look at A New Hasidism: Roots and the second volume Branches by Arthur Green and Ariel Mayse. See also The Receiving: Reclaiming Jewish Women’s Wisdom by Tirzah Firestone.

9. Ashlag-Inspired Organizations

(Begins 20th century CE)

Rabbi Yehuda Ashlag was an influential 20th century Kabbalist who was born in Poland and produced most of his writing in Eretz Yisrael.3 Raised Hasidic and influenced by Lurianic Kabbalah, he also read Marx and other secular philosophies of his era. Ashlag wanted to make Kabbalah more accessible to learned Jews, beyond the very limited circles that were studying it during his time. After several generations, his students have formed many well-known organizations that trace their Kabbalistic style to Ashlag.

The most notable of these institutions is the Kabbalah Centre started by Rabbi Phillip Berg in the late 20th century. Berg gradually extended his Kabbalistic teachings more broadly to women, non-religious Jews, and eventually to people of any ethnicity or religion. He was known to teach celebrities including, most famously, the pop singer Madonna. Though Rabbi Berg came from a Kabbalistic lineage, his organization has been publicly criticized because of what critics saw as his profit-oriented approach to teaching and his focus on more superstitious elements of the tradition. Another Ashlag-Inspired Organization is Bnei Baruch which is centred in Petah Tikvah, Israel, and has tens of thousands of students within the country and abroad.

Similarly to Contemporary Orthodox Jewish Mysticism, the Ashlag-Inspired Kabbalists tend not to include the findings of historical scholarship in their teachings and commentaries.

One example of this form of Kabbalah can be found in The 72 Names of God by Yehuda Berg.

10. Christian Kabbalah

(Begins 15th century CE)

Often spelled with a “C” to distinguish it from Jewish Kabbalah, it started with Christians who took an interest in Medieval Kabbalah. They translated and interpreted works such as the Zohar in light of Christian theology. These early interpreters believed in the antiquity of Kabbalah (e.g. they believed the Zohar’s teachings originated long before the medieval age). Christian Kabbalists understood Kabbalah as universal perennial wisdom that contained Christian elements and they used it partially as a means of proselytization.

For examples of Christian kabbalistic thought, see the 15th century 900 Theses by Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. He believed this book synthesized all of Western thought, including Kabbalah.

11. Occultist Kabbalah

(Begins 19th century CE)

Occultism, loosely defined, is the esoteric interest in supernatural forces, magic, intuition, and mysticism. Occultist groups like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (Founded in London) and the Theosophical Society (Founded in New York) took great interest in Kabbalah. Most of their studies derived from Christian Kabbalistic sources and they understood this body of teachings to be a perennial and magical spiritual system. The late 19th century Occultists spelled Kabbalah with a “Q” and used specific concepts (such as the Sefirot) as the basis for a classification system of spiritual phenomena from many cultures. They also incorporated Kabbalah into practical guidance for navigating interactions with spirits, demons, and practitioners of negative magic.

Madame Blavatsky, the founder of the Theosophical Society, asserted that Kabbalah had been misconstrued by the Jews and was actually of Greek and Egyptian origin (one view — among many held by the early Occultists — that is not supported by academic scholarship of Kabbalah).

For examples of Occultist Kabbalah see Alister Crowley’s 777 and Dion Fortune’s The Mystical Qabalah.

12. New Age and Spiritual but Not Religious Kabbalah

(Begins 19th century CE)

This non-centrally organized form incorporates elements of Occultist Kabbalah, the Academic Study of Kabbalah, Ashlag-Inspired Organizations, Contemporary Orthodox Jewish Mysticism, and Non-Denomenational Jewish Mysticism. It sees Kabbalah as a perennial spiritual system that articulates the same universal message at the heart of all religions. It follows that Kabbalah need not be constrained to ethnicity or religion; it is for all people. In this contemporary form, it is common for elements of Kabbalah, such as the Sefirot, to be compared with other mystical systems, such as the Chakras from Yoga, usually emphasizing their similarities over their differences.

An example of this 12th type can be seen in the Kabala Oracle Cards created by Deepak Chopra, Michael Zapolin, and Alys Yablon. Another example in the context of healing is Sound VIbrational Healing, Vol #1 Chakra/Kabbalah by Sunny Heartley.

In summary, these twelve groups constitute a fairly comprehensive look at what different people mean when they say “Kabbalah.” Each group has unique characteristics and occupies a different space in the spiritual landscape of the past and present. Although I personally have a strong preference for contemporary forms of Kabbalah which articulate an accurate version of its history, I know that each camp has something legitimate and helpful to share.

Who is wise? The one who learns from everyone.

— ben zoma, 2nd century jewish sage (ce)

There are some additional groups who do not fit neatly into any of these categories, including very new schools just emerging. Regardless of these few exceptions, if you encounter people or institutions teaching Kabbalah today, it is very likely you will be able to trace them back to one or more of these 12.

To learn more about Kabbalah and Hasidism read Embodied Kabbalah: Jewish Mysticism for All People, an accessible guide to a thousand years of grounded spirituality.

The information about the history of Jewish mysticism was largely adapted from Embodied Kabbalah.

Thanks to Dr. Boaz Huss and especially for his article Academic Study of Kabbalah and Occultist Kabballah for information about Occultist and Christian Kabbalah. Also, thanks to the scholarship of Dr. Jody Myers and her book Kabbalah and the Spiritual Quest for information about the Kabbalah Centre, New Age and Spiritual but Not Religious Kabbalah, and Yehuda Ashlag.

1 If you’re wondering why I was reading Psychic Self-Defense, I’ll share more about that in a future blog post around Halloween time.

2 Each type of Kabbalah is given only a start date in this post. To some degree they have all continued to exist until present day, albeit in new forms. In rabbinic understanding, Israelite Prophecy is very often considered to have ended in the 6th century BCE, which is why it is given a “before” date.

3 The Land of Israel in Hebrew. This is the ancient way of referring to that land in Israelite and Jewish literature.